“In an ever-changing, incomprehensible world the masses had reached the point where they would, at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and that nothing was true.” — Hannah Arendt

I doubt I am alone in my feeling that every day, things get imperceptibly worse, a sense that the water is slowly being boiled. The temperature is rising, both figuratively and literally. I also doubt that I am alone in my capacity to ignore that nagging thought when things are, by some metric, getting better too. My stock portfolio is up. Any question I have is answerable immediately. Everything is so convenient. I don't fully trust my judgement on the direction of progress, as people have always looked back to the Golden Age of yesterday while lamenting the present. T.S. Eliot wrote, “We can assert with some confidence that our own period is one of decline; that the standards of culture are lower than they were fifty years ago; and that the evidences of this decline are visible in every department of human activity.” He stands in a long succession of thinkers lamenting the same.

Yet, few would disagree that we are in the midst of an unfolding polycrisis. Our planet is crossing a climate threshold from which we may not return. Income inequality has reached historic extremes, with rich oligopolists harboring more power than nation-states. Democracy is cratering in many places while authoritarianism reappears with eerily familiar aggression. We’ve reached a stage where labor defines meaning-making in our lives, even as the institutions built on that labor prepare to offload it onto cheaper, more efficient systems. We have arrived here through a tragedy of the commons, a diffusion of responsibility belonging to everyone and no one at the same time.

My sense is that some combination of unconscious incentives, over-optimization/overfitting, and machinic desire have colluded to grant us the current moment.

From a game theoretic perspective in most human systems, short-term rewards overpower long-term judgment. “Nothing is as important as you think it is while you are thinking about it.” The problem with slow violence, as Rob Nixon calls it (his recent book is a very good exposition of the subject), is that it belongs to the realm of fact rather than story. Its harm accumulates in increments too small to gather attention, leaving communities to suffer consequences that never rise to the level of a headline.

Violence motivates action through emotion or the shock of catastrophe. Slow violence offers neither. It is the story of a complex, multivariable system unfolding incrementally, often generationally, and if not, still slow enough that most people barely notice, while broad scientific consensus and mountains of data fail to prompt action. Convincing people of the urgency of addressing slow violence is difficult in an age of declining attention spans (a point I’ll return to later), so instead, we’re left with a sense that the shoe is about to drop and we aren’t able to articulate precisely why.

I once looked to placid commentaries like The Better Angels of Our Nature to become convinced that progress has delivered gains in health, safety, and comfort, and that everything was getting better. By many measures, an ordinary person today lives better than a king did two hundred years ago. Increasingly, I believe the real story is much more complex. You can have a world where metrics of progress are getting better while simultaneously hurtling towards disaster.

To understand why things seem to improve, while existential crises remain invisible until it is too late, we need to look less at ideology and more at the mechanics of perception itself.

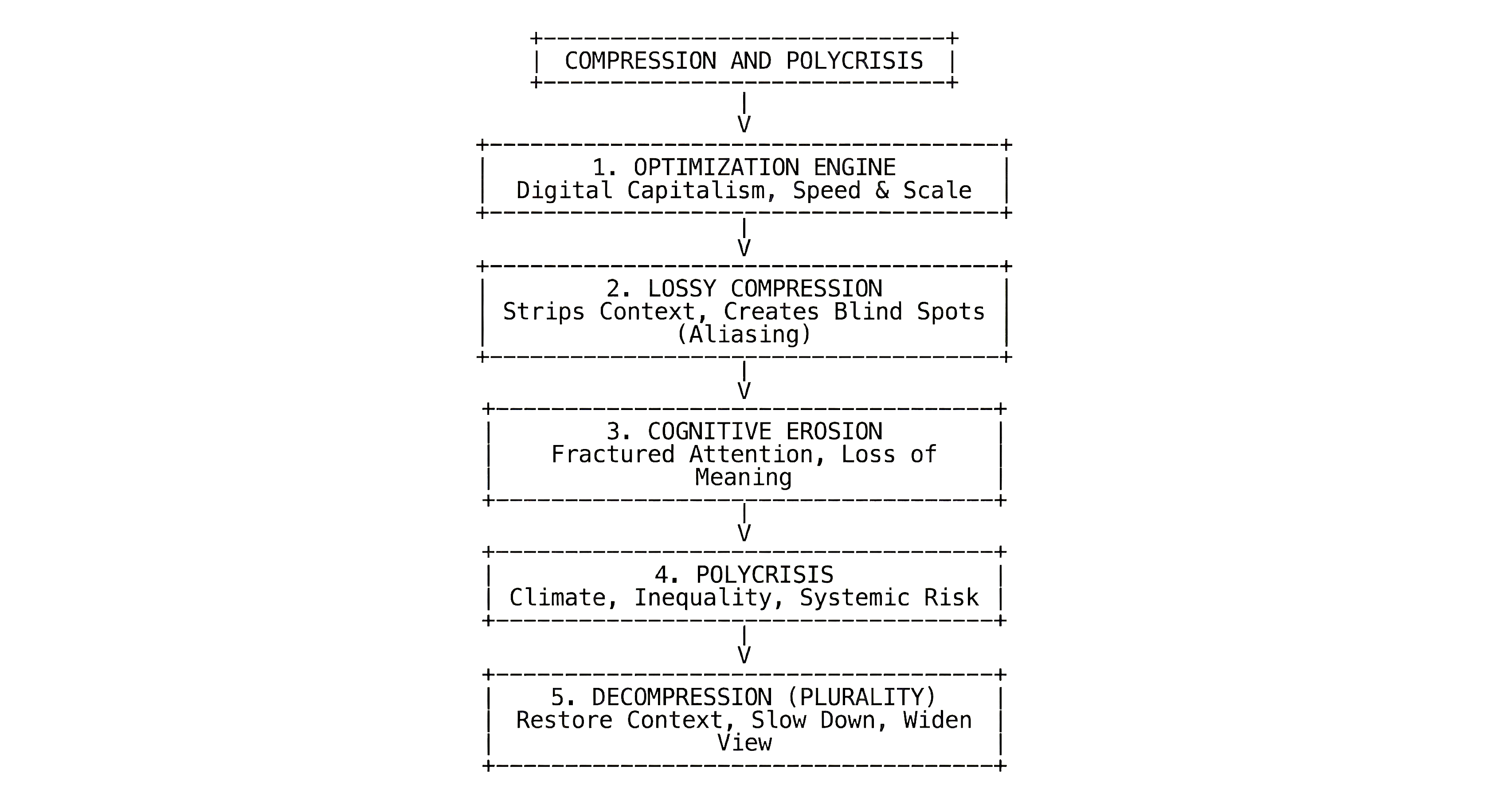

I believe much of it can be analogized through information theory with terms like compression and aliasing. In simple terms, capitalism and efficiency gains operate through compression. Labor compresses production capacity. LLMs compress information. All lead to efficiency gains, but at some cost. Compression can be lossy, and much of what is lost is considered noise. However, if you compress enough information for a long enough time, you might find that much of the noise that was discarded was actually quite critical.

If you try to record a high-frequency signal (like a fast violin note) with a low-frequency recorder, you get a false recording or aliasing. The recorder hallucinates a new, lower note that doesn't actually exist. Our civilization is undergoing temporal aliasing. The slow violence of climate change, institutional decay, and topsoil erosion operates on a frequency of decades. The sensor networks we use to govern stock markets, election cycles, and social media trends sample reality at a frequency of milliseconds to months. By the time these high-speed sensors capture the low-speed signal of ecological collapse, they have distorted it into noise or short-term volatility.

This blindness is compounded by a violation of cybernetics known as Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety. This law states that for a system to be stable, the control mechanism must have at least as many states (or as much complexity) as the environment it tries to control. If the environment is complex and the controller is simple, the system must fail.

Our world is a working example of what happens when Ashby’s Law breaks down. Digital capitalism is an engine of simplification. It reduces the infinite variety of the physical world into the low-variety language of prices and engagement metrics to achieve scale. While scale is itself a form of progress, achieving it comes at the cost of introducing lossy compression, shaving off the inefficient local context that makes systems resilient. GDP and QALYs, which we use to tell the story of progress, are very lossy metrics. You can absolutely create a world where people are living longer with exponentially more suffering or one where GDP is growing alongside income inequality.

Compounding this issue, I believe the metacrisis above the polycrisis is one of attention. Every serious problem we face demands sustained focus and a willingness to trade short-term comfort for long-term stability. This is difficult when the systems that structure our lives and wire our brains, such as smartphones, LLMs, TikTok, are steadily eroding our attention spans to a degree unprecedented in human history.

So ultimately, my view is that the unconscious machinic desire of capitalism, the set of incentives at play and the uncontrollable momentum it creates, is locked into extractive patterns that are hard to break. Getting out of this pattern requires the ability to hold contradictions and to cooperate across sharp disagreement. It requires a kind of pluralistic politics that depends on the capacities that short-form engagement platforms destroy, things like imagination, sustained empathy, and the courage to keep seeing opponents as human. Resistance requires attention.

This all amounts to a systemic aesthetic failure with a crisis of meaning emerging from lossy compression. To manage the staggering complexity of the world, our civilization has become very good at dimensional reduction. We strip the noise of context from our reality to make it legible to our control systems. But in cybernetics, the stability of a system depends on the quality of its feedback loops. By aggressively compressing the signal of reality into fast data, we have inadvertently filtered out critical information required for survival.

If this framing is correct, the mechanism behind the polycrisis is a signal-to-noise inversion where the things that matter most (resilience, trust, ecological limits) are treated as friction to be smoothed away, while the things that matter least (engagement, quarterly growth) are amplified into existential imperatives. This compression shapes us and shortens our attention spans to match the speed of our machines. We lose the capacity to engage the slow and the contradictory because our internal processors have been overclocked to handle a stream of context-free stimulation. We become lossy copies of ourselves.

I think the likely antidote to this compression is a deliberate decompression of our future. Navigating the polycrisis requires a new kind of politics and technology designed for plurality, basically systems that are context-aware and refuse to collapse complex values into single metrics. This is a difficult task in the context of a system that selects ruthlessly for efficiency. We need to rebuild the capacity for thick data, reintroducing the friction of context back into our decision-making loops. If the last century was defined by the drive to optimize and compress, the next should be defined by the ambition to restore resolution to our view of the world.